| To understand

the tremendous popularity and growth Gothard’s seminar enjoyed in the late

1960s and early ’70s, you have to know something about the social turmoil

of those years. Gothard titled

his seminar, “Institute in Basic Youth Conflicts,” and it would have been

difficult to find a more marketable name for many parents who felt helpless

to deal with strange new influences over their children. Conflict

between youths and the over-30 generation dominated American society, and

even caused problems in other countries.

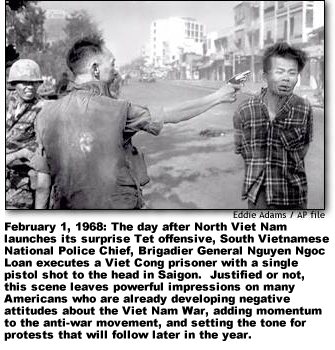

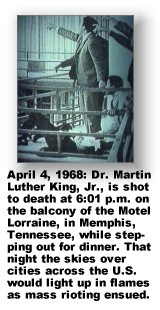

By 1967 the United States looked as though it was about to become a wholly-owned subsidiary of The Baby Boom Generation. Fully 50% of all Americans were 21 or younger. By the end of 1968 the ability of this age-group and those who influenced them to turn the socio-political landscape upside-down and change the direction of governments had been dramatically demonstrated on the streets, in newspapers, and on TV screens. In 1968 it seemed as though “Murphy’s Law” was operating in full force. Everything that could go wrong did, and at the worst possible moments. As the year began, “The Baby Book Doctor,” Dr. Benjamin Spock was indicted with four others on January 5 for conspiring to encourage draft law violations. For older Americans Spock became a symbol of the problem of “permisiveness” in society. Perhaps the real problem, many speculated, was that millions of youngsters were simply spoiled by Spock’s methods, and current expressions of civil disobedience were merely mass post-adolescent temper tantrums. But events on the world scene soon challenged such superficial analysis. On January 23 North Korea captured a U.S. Navy spy boat, the USS Pueblo, and the ensuing 11-month crisis exposed American foreign policy to worldwide scorn. One week later the North Vietnamese launched their surprise Tet offensive. While it was eventually turned back by American and South Vietnamese forces, it gave a major psychological and propaganda victory to North Viet Nam and the Viet Cong rebels in the south. On the second day of Tet offensive fighting, an American photographer snapped a picture of a South Vietnamese general summarily executing a youthful Viet Cong rebel on the streets of Saigon. Despite the extreme circumstances of the event, and the possibility that the young man had killed a Saigon policeman and his entire family, the photograph triggered horrified reactions in the U.S. A few days later an unidentified U.S. major was quoted in newspapers around the world as saying, “It became necessary to destroy the town [of Ben Tre] to save it.” Walter Cronkite visited Viet Nam to view the aftermath of the Tet offensive, and his highly critical February 27 report on a CBS TV special contradicted offical U.S. government statements on the progress of the war. In two weeks the Tet offensive produced the highest U.S. casualty-toll thus far in the war: 543 Americans killed, 2,547 wounded. It forced Americans at home to face the question, “Is this really the kind of war we should be involved in?” The answers people gave polarized American society for years to come. What most people did not know — and would not know for more than a year — was that on March 16 U.S. ground troops from Charlie Company massacred more than 500 Vietnamese men, women and children, including infants and the elderly in the hamlet of My Lai. The three-hour rampage was finally ended when three American helicopter pilots noticed the slaughter and positioned their crafts between the troops and the fleeing Vietnamese, later carrying off a handful of wounded to safety. The soldiers of Charlie Company were convinced, and would later testify at court-martial, that they were acting strictly on orders. But as tempers and rhetoric intensified over what was known about the war, the assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy removed from the scene two leaders who were noted for promoting non-violent approaches to social and political change. So by the time the Democratic National Convention assembled in Chicago that August, the atmosphere had been poisoned, and personalities who could have quelled the violence were gone. |

|